At the heart of this extraordinary growth is an American revolution. In the Premier League’s inaugural season, football was still in recovery from the horrors of the stadium disasters at Hillsborough and Heysel. Owners tended to be from the local area and with a business background. The only foreign owner was Sam Hamman at Wimbledon, a Lebanese millionaire who bought the club on a whim having reportedly been much more interested in tennis. The season ended with Manchester United (under Alex Ferguson) winning the English game’s top league for the first time in 26 years.

Now, if the Texas-based Friedkin Group’s recent deal to buy Everton goes through, 11 of the 20 Premier League clubs will be controlled or part-owned by American investors. The US – long seen as football’s final frontier when it comes to the men’s game – suddenly can’t get enough of English “soccer”.

Four of the Premier League’s “big six” are American-owned – Manchester United, Liverpool, Arsenal and Chelsea – while a fifth, Manchester City, has a significant US minority shareholding. Aston Villa, Fulham, Bournemouth, Crystal Palace, West Ham and Ipswich Town also have varying degrees of American ownership.

And it’s not even just the glamour clubs at the top of the tree. American investment has also been significant lower down the football pyramid, led by the high-profile acquisition of then non-league Wrexham by Hollywood actors Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenny, and Birmingham City’s purchase by US investors including seven-time Super Bowl winner Tom Brady. American investment in football has reached places as geographically diverse as Carlisle and Crawley in England, and Aberdeen and Edinburgh in Scotland.

So why the American obsession with English football? And how real are concerns that these US owners could collude to “Americanise” the traditions of the Premier League – whether by reducing the risk of relegation, introducing some form of “draft pick” system, or moving matches and even clubs to other cities?

The Premier League’s first US owner

Manchester United was the first Premier League club to come under American ownership – after a row about a horse.

In 2005, United was owned by a variety of investors including Irish businessmen and racehorse owners John Magnier and J.P. McManus. Their erstwhile friend Ferguson, the United manager, thought he co-owned the champion racehorse Rock of Gibraltar with them – a stallion worth millions in stud rights. They disagreed – and their bitter dispute was such that Magnier and McManus decided to sell their shares in the football club.

The Miami-based Glazer family – already involved in sport as owners of NFL franchise the Tampa Bay Buccaneers – had already been buying up small tranches of shares in United, but the sudden availability of the Irish shares allowed Malcolm Glazer to acquire a controlling stake for £790 million (around £1.5 billion at today’s prices).

The fact Glazer did not actually have sufficient funds to pay for these shares was a solvable problem. In the some-might-say commercially naive world of top-flight English football before the Premier League, Manchester United was a club without debt, paying its way without leveraging its position as one of the world’s most famous football clubs. Glazer saw the opportunity this presented and arranged a leveraged buy-out (LBO), whereby the football club borrowed more than £600 million secured on its own assets to, in effect, “buy itself” in 2005.

Despite the need to meet the high interest costs to fund the LBO, United continued winning trophies under Ferguson – including three Premier League titles in a row in 2007, 2008 and 2009, as well as a Champions League victory in 2008. Amid this success, the club felt that ticket prices were too low and set about increasing them, with matchday revenue increasing from £66 million in 2004/05 to over £101 million by 2007/08.

Commercial income was another area the Glazers were keen to increase. United set up offices in London and adopted a global approach to finding new official branding deals ranging from snacks to tractor and tyre suppliers – doubling revenues from this income source too.

But in this new, more aggressive world of “sweating the asset”, the debts lingered – and most United fans remained deeply suspicious of their American owners. (Following their father’s death in 2014, the club was co-owned by his six children, with brothers Avram and Joel Glazer becoming co-chairmen.)

Today, despite its partial listing on the New York Stock Exchange and the February 2024 sale of 27.7% of the club to British billionaire Sir Jim Ratcliffe for a reputed £1.25 billion, United still has borrowings of more than £546 million, having paid cumulative interest costs of £969 million since the takeover in 2005. But with the club now valued at US$6.55 billion (around £5bn), it represents a very smart investment for the Glazer family.

Indeed, while the prices being paid for football clubs across Europe have reached record levels, they are still seen as cheap investments compared with US sports’ leading franchises. Forbes’s annual list of the world’s most valuable sports teams has American football (NFL), baseball (MLB) and basketball (NBA) teams occupying the top ten positions, with only three Premier League clubs – Manchester United, Liverpool and Manchester City – in the top 50.

With NFL teams having an average franchise value of US$5.1 billion and NBA $3.9 billion, many English football clubs still look like a bargain from the other side of the pond.

The risk of relegation

The latest to join this US bandwagon, the Friedkin Group – a Texas-based portfolio of companies run by American businessman and film producer Dan Friedkin – is reported to have offered £400m to buy Everton, despite the club’s poor financial state.

“The Toffees” have been hit by loss of sponsorships as well as two sets of points deductions for breaching the Premier League’s financial rules, leading to revenue losses from lower league positions. While the new stadium being built at Liverpool’s Bramley-Moore dock has been yet another financial constraint, it will at least increase matchday income from the start of next season.

A wider reason for the relative bargain in valuations of European football clubs is the risk of relegation – something that is not part of the closed leagues of most US sports. While the threat of relegation (and promise of promotion) has always been an integral part of English and European football, the jeopardy this brings for supporters – and a club’s finances – does not exist in the NFL, NBA, Major League Soccer and similar competitions.

The Premier League, with its three relegation spots at the end of each season, has featured 51 different clubs since it launched in 1992. Only six clubs – Arsenal, Spurs, Chelsea, Manchester United, Liverpool and Everton – have been ever present, with Arsenal now approaching 100 years of consecutive top-flight football.

Other Premier League clubs have experienced the dramatic cost-benefit of relegation and promotion. Oldham Athletic, who were in the Premier League for its first two seasons, now languish in the fifth tier of the game, outside the English Football League (EFL). In contrast, Luton Town, who were in the fifth tier as recently as 2014, were promoted to the Premier League in 2023 – only to be relegated at the end of last season.

While it is difficult to compare football clubs with basketball and American football teams, the financial difference between having an open league, with relegation, and a closed league becomes apparent when you look at women’s football on both sides of the Atlantic.

Angel City, a women’s soccer team based in Los Angeles, only entered the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) in 2022 and is yet to win an NWSL trophy. But last month, the club was sold for US$250 million (£188m) to Disney’s CEO Bob Iger and TV journalist Willow Bay – the most expensive takeover in the history of women’s professional sport.

In comparison, Chelsea – seven-time winners of the English Women’s Super League and one of the most successful sides in Europe – valued its women’s team at £150 million ($US196m) earlier this summer. While there are a number of factors to this price differential, the confidence that Angel City will always be a member of the big league of US soccer clubs – and share very equally in its revenue – will have made its new owners very confident in the long-term soundness of their deal.

While interest in, and hence value of, the WSL is now growing fast, the women’s game in England is dwarfed by viewer ratings for the Premier League – the most watched sporting league in the world, viewed by an estimated 1.87 billion people every week across 189 countries.

These figures dwarf even the NFL which, while currently still the most valuable of all sporting leagues in terms of its broadcasting deals, must be looking at the growth of the Premier League with some jealousy. This may explain why some US franchise owners, such as Stan Kroenke, the Glazer family, Fenway Sports Group and Billy Foley, have subsequently purchased Premier League football clubs.

Ironically, for many spectators around the world, it is the intensity and competitiveness of most Premier League matches – brought on in part by the threat of relegation and prize of European qualification – that makes it so captivating. However, billionaire investors like guaranteed numbers and dislike risk – especially the degree of financial risk that exists in the Premier League and English Football League.

European not-so-Super League

In April 2021, 12 leading European clubs (six from England plus three each from Spain and Italy) announced the creation of the European Super League (ESL). This new mid-week competition was to be a high-revenue generating, closed competition with (eventually) 15 permanent teams and five annual additions qualifying from Europe. According to one of the driving forces behind the plan, Manchester United co-chairman Joel Glazer:

By bringing together the world’s greatest clubs and players to play each other throughout the season, the Super League will open a new chapter for European football, ensuring world-class competition and facilities, and increased financial support for the wider football pyramid.

The problem facing the Premier League’s “big six” clubs – and their ambitious owners – is there are currently only four slots available to play in the Champions League. So, their thinking went, why not take away the risk of not qualifying? However, the proposal was swiftly condemned by fans around Europe, together with football’s governing bodies and leagues – all of whom saw the ESL proposal as a threat to the quality and integrity of their domestic leagues. Following some large fan protests, including at Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge, Manchester City was the first club to withdraw – followed, within a couple of days, by the rest of the English clubs.

Under the terms of the ESL proposals, founding member clubs would have been guaranteed participation in the competition forever. Guaranteed participation means guaranteed revenues. The current financial gap between the “big six” and the other members of the Premier League, which in 2022/23 averaged £396 million, would have widened rapidly.

For example, these clubs would have been able to sell the broadcast rights for some of their ESL home fixtures direct to fans, instead of via a broadcaster. All of a sudden, that database of fans who have downloaded the official club app, or are on a mailing list, becomes far more valuable. These are the people most willing to watch their favourite team on a pay-per-view basis, further increasing revenues.

At the same time, a planned ESL wage cap would have stopped players taking all these increased revenues in the form of higher wages, allowing these clubs to become more profitable and their ownership even more lucrative.

American-owned Manchester United and Liverpool had previously tried to enhance the value of their investments during the COVID lockdowns era via ProjectBig Picture – proposals to reduce the size of the Premier League and scrap one of the two domestic cup competitions, thus freeing up time for the bigger clubs to arrange more lucrative tours and European matches against high-profile opposition.

Most importantly, Project Big Picture would have resulted in changing the governance of the domestic game. Under its proposals, the “big six” clubs would have enjoyed enhanced voting rights, and therefore been able to significantly influence how the domestic game was governed.

Any attempt to increase the concentration of power raises concerns of lower competitive balance, whereby fewer teams are in the running to win the title and fewer games are meaningful. This is a problem facing some other major European football leagues including France’s Ligue 1, where interest among broadcasters has dwindled amid the perceived dominance of Paris St-Germain.

So while to date, American-led attempts to change the structure of the Premier League have been foiled, it’s unlikely such ideas have gone away for good. The near-universal fear of fans – even those who welcome an injection of extra cash from a new billionaire owner – is that the spectacle of the league will only be diminished if such plans ever succeed.

And there is evidence from the women’s game that the US closed league format is coming under more pressure from football’s global forces. The NWSL recently announced it is removing the draft system that is designed (as with the NFL and NBA) to build in jeopardy and competitive balance when there is no risk of relegation.

Top US women’s football clubs are losing some of their leading players to other leagues, in part because European clubs are not bound by the same artificial rules of employment. In a truly global professional sport such as football, international competition will always tend to destabilise closed leagues.

Why do they keep buying these clubs?

Does this mean that American and other wealthy owners of Premier League clubs seeking to reduce their risks are ultimately fighting a losing battle? And if so, given the potential risks involved in owning a football club – both financial and even personal – why do they keep buying them?

The motivations are part-financial, part technological and, as has always been the case with sports ownership, part-vanity.

The American economy has grown far faster than that of the EU or UK in recent years. Consequently, there are many beneficiaries of this growth who have surplus cash, and here football becomes an attractive proposition. In fact, football clubs are more resilient to recessions than other industries, holding their value better as they are effectively monopoly suppliers for their fans who have brand loyalty that exists in few other industries.

From 1993 to 2018, a period during which the UK economy more than doubled, the total value of Premier League clubs grew 30 times larger. And many fans are tied to supporting one club, helping to make the biggest clubs more resilient to economic changes than other industries. While football, like many parts of the entertainment industry, was hit by lockdown during Covid, no clubs went out of business, despite the challenges of matches being played in empty stadiums.

Added to this, the exchange rates for US dollars have been very favourable until recently, making US investments in the UK and Europe cheaper for American investors.

So, while Manchester United fans would argue that the Glazer family have not been good for the club, United has been good for the Glazers. And Fenway Sports Group (FSG), who bought Liverpool for £300 million in 2010, have recouped almost all of that money in smaller share sales while remaining majority owners of Liverpool.

Despite this, the £2.5 billion price paid for Chelsea by the US Clearlake-Todd Boehly consortium in May 2022 took markets by surprise.

The sale – which came after the UK government froze the assets of the club’s Russian oligarch owner, Roman Abramovich, following the invasion of Ukraine – went through less than a year after Newcastle United had been sold by Sports Direct founder Mike Ashley to the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund for £305 million – approximately twice that club’s annual revenues. Yet Clearlake-Boehly were willing to pay over five times Chelsea’s annual revenues to acquire the club, even though it was in a precarious financial position.

Clearlake is a private equity group whose main aim is to make profits for their investors. But unlike most such investors, who tend to focus on cost-cutting, the Chelsea ownership came in with a high-spending strategy using new financial structuring ideas, such as offering longer player contracts to avoid falling foul of football’s profitability and sustainability rules (although this loophole has since been closed with Uefa, European football’s governing body, limiting contract lengths for financial regulation purposes to five years).

Chelsea’s location in the one of the most expensive areas of London, combined with its on-field success under Abramovich, all added to the attraction, of course. But there are other reasons why Clearlake, along with billionaire businessman Boehly, were willing to stump up so much for the club.

From Hollywood to the metaverse

While some British football fans may have viewed the Ted Lasso TV show as an enjoyable if slightly twee fictional account of American involvement in English soccer, it has enhanced the attraction of the sport in the US. So too Welcome To Wrexham – the fly-on-the-wall series covering the (to date) two promotions of Wales’s oldest football club under the unlikely Hollywood stewardship of Reynolds and McElhenney.

But as well as football offering one of increasingly few “live shared TV experiences” that carry lucrative advertising slots, there may also be more opportunity for more behind-the-scenes coverage of the Premier League – as has long been seen in US coverage of NBA games, for example, where players are interviewed in the locker room straight after games.

According to Manchester United’s latest annual report, the club now has a “global community of 1.1 billion fans and followers”. Such numbers mean its owners, and many others, are bullish about the potential of the metaverse in terms of offering a matchday experience that could be similar to attending a match, without physically travelling to Manchester.

Their neighbours Manchester City, part-owned by American private equity company Silverlake, broke new (virtual) ground by signing a metaverse deal with Sony in 2022. Virtual reality could give fans around the world the feeling of attending a live match, sitting next to their friends and singing along with the rest of the crowd (for a pay-per-view fee).

Some investors are even confident that advancements in Abba-style avatar technology could one day allow fans to watch live 3D simulations of Premier League matches in stadiums all over the world. Having first-mover advantage by being in the elite club of owners who can make use of such technology could prove ever more rewarding.

More immediately, there are some indications that competitive matches involving England’s top men’s football teams could soon take place in US or other venues. Boehly, Chelsea’s co-owner, has already suggested adopting some US sports staples such as an All-Star match to further boost revenues. Indeed, back in 2008, the Premier League tentatively discussed a “39th game” taking place overseas, but that idea was quickly shelved.

The American owners of Birmingham City were keen to play this season’s EFL League One match against Wrexham in the US, but again this proposal did not get far. Liverpool’s chairman Tom Werner says he is determined to see matches take place overseas, and recent changes to world governing body Fifa’s rulebook could make it easier for this proposal to succeed.

The potential benefits of hosting games overseas include higher matchday revenues, increased brand awareness, and enhanced broadcast rights. While there is likely to be significant opposition from local fans, at least American owners know they would not face the same hostility about rising matchday prices in the US as they have encountered in England.

When the Argentinian legend Lionel Messi signed for new MLS franchise Inter Miami in 2023, season ticket prices nearly doubled on his account. And while there is vocal opposition to higher ticket prices in England, this is not borne out in terms of lower attendances for matches against high-calibre opposition – as evidenced by Aston Villa charging up to £97 for last week’s Champions League meeting with Bayern Munich.

Villa’s director of operations, Chris Heck, defended the prices by saying that difficult decisions had to be made if the club was to be competitive.

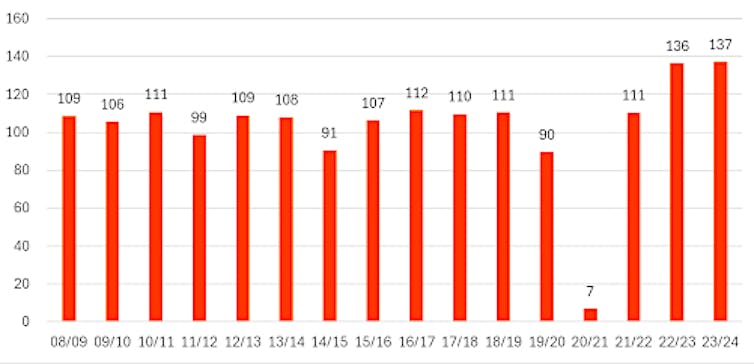

Manchester United’s matchday revenue per EPL season (£m)

For much of the 2010s, with broadcast revenues increasing rapidly, many Premier League owners made little effort to stoke hostilities with their loyal fan bases by putting up ticket prices. Indeed, Manchester United generated little more from matchday income in the 2021-22 season, as football emerged from the pandemic, than the club had in 2010-11 (see chart above).

However, this uneasy truce between fans and owners has ceased. The relative flatlining of broadcast revenues since 2017, along with cost control rules that are starting to affect clubs’ ability to spend money on player signings and wages, has changed club appetites for dampened ticket prices. This has resulted in noticeable rises in individual ticket and season ticket prices by some clubs.

However, season ticket and other local “legacy” fans generate little money compared with the more lucrative overseas and tourist fans. They may only watch their favourite team live once a season, but when they visit, they are far more likely not only to pay higher matchday prices, but to spend more on merchandise, catering and other offerings from the club.

Today’s breed of commercially aware, profit-seeking US Premier League owners – pioneered by the Glazer family, who saw that “sweating the asset” meant more than watching football players sprinting hard – understand there is a lot more value to come from English football teams. The clubs’ loyal local supporters may not like it, but English football’s American-led revolution is not done yet.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Kieran Maguire, Senior Teacher in Accountancy and member of Football Industries Group, University of Liverpool and Christina Philippou, Associate Professor in Accounting and Sport Finance, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.